One of the private partners is an African company attributed by a number of international authorities with being a "dark treasury" of the Congolese regime, a satellite company through which politicians and technocrats channel money abroad to buy luxury goods. The Italian investors are not known or visible publicly: their names are hidden behind complicated networks of offshore companies, now unveiled by L'Espresso in a new chapter of the Paradise Papers.

Our investigative piece, which is based on confidential documents obtained from tax havens, leads to four individuals, two men and two women, with one thing in common: they are all connected, directly or indirectly, to the top executives of ENI, the Italian government-controlled gas and oil behemoth. The most important public company in Italy has long been at the center of several probes of the judiciary with very serious charges of corruption to the detriment of other African nations, such as Algeria and Nigeria.

PAY 15, EARN 430

The gas field at the center of this case is called Marine XI and is worth at least $2.5 billion (€2 billion). L'Espresso identified the actual owners by canvassing over 700 documents contained in the Paradise Papers, the gigantic archive of corporate documents that the German daily Süddeutsche Zeitung shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) of which our weekly is a member.

Since becoming president in 1979, former general Denis Sassou Nguesso has ruled over Congo and its capital Brazzaville with rolling mandates for decades now. The former French colony is rich in gas and oil, but the Congolese are very poor: according to UN data, half of the population survives on little more than a dollar a day. In France, Great Britain and other countries, the Congolese regime has repeatedly been accused of blatant corruption schemes involving the oil companies and the president's circle.

THREE ANONIMOUS ITALIANS

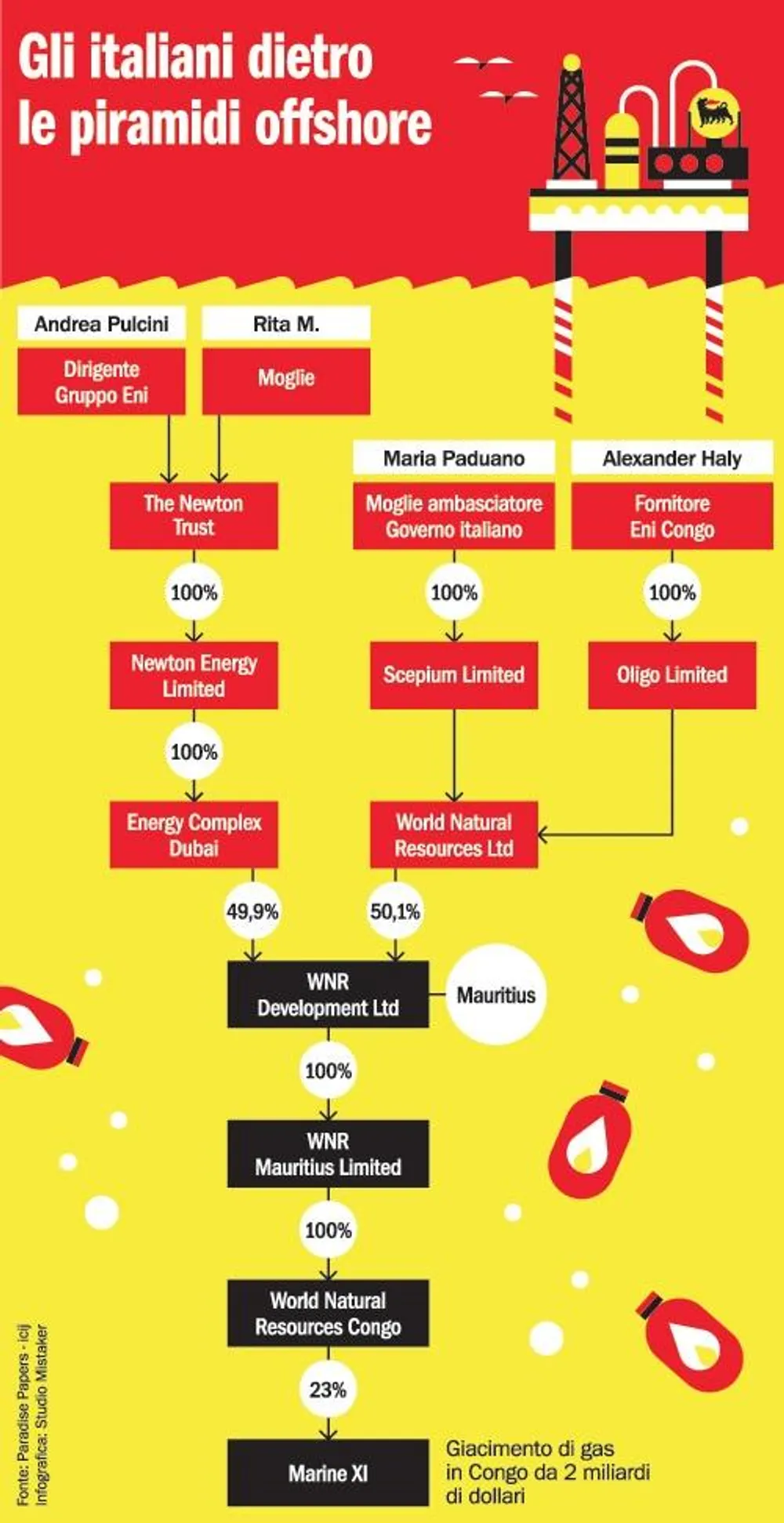

Managing the undersea field Marine XI are Soco, a London-listed oil company, in partnership with Petro Vietnam, another large foreign energy company, and SNPC, the Congolese state oil company, which appears to be happy to hold only a minority stake. In March 2013, a secretive newly incorporated company, World Natural Resources (WNR) Congo, entered the deal buying a 23% stake for just $15 million. WNR Congo is entirely owned by four anonymous shareholders. The graph below shows its controlling structure.

And here is where the Italians come into play with their four offshore companies and their 23% controlling stake of the mega-gas field. Their part alone is worth $430 million, according to internal company documents — but the Italians offshore companies acquired it for just $15 million. And with no company money thanks to a covered loan provided by a Swiss-based energy group.

The two companies that own the gas field are registered in the Mauritius Islands where “the maximum tax rate is 3%”, as Appleby consultant firm explains. To find out who the real owners were, we had to reverse-retrace three other corporate pyramids consisting of British trusts and anonymous companies scattered between New Zealand and Dubai. The documents show that the first shareholder is an Italian manager of ENI Group, who together with his wife controls a 49.9% stake of WNR Congo. The remaining 50.1% is in the hands of two partners: one is an Italian woman with strong personal ties to the Italian Foreign Ministry and to ENI's top floor; the other a British executive head of several contractor-supply companies to the Italian oil group.

AN AGIP-BRANDED MANAGER

Founder of the two Mauritius “safe”-companies is Andrea Pulcini, an Italian manager with a significant track record in ENI group. From 1994 to 2005 he was among the top executive managers of AGIP Trading Services UK, a satellite company taking care of the Italian energy giant’s businesses in strategic London — his company was later absorbed into the parent company ENI and became its most important division. The Register of Italian Companies shows Mr. Pulcini as holding still the capacity of ENI’s attorney (i.e. its official representative) since 1999. The documents do not specify whether he is still on ENI’s payroll or on that of any of the satellite foreign companies.

As documented by the Paradise Papers, it is clear that Mr. Pulcini owns personally Energy Complex, a company in Dubai operating in the same sector as ENI: gas and oil. This is the private company that secretly bought the gas field in Congo. The manager's personal financial headquarters are, though, in New Zealand. They go by the name of Newton Trust and are managed by Swiss professionals of the award-winning firm Tax & Finance (currently under investigation in Milan for alleged international tax evasion to the benefit of other Italian entrepreneurs).

Between March and July 2013, ENI’s representative, Mr. Pulcini, was in a hurry to incorporate the companies in the Mauritius Islands through which he then initially got to fully control WNR Congo. His stock was co-owned with his wife, Rita M., now separated from him and registered from inception as "secondary" beneficiary after her husband. Once the field was bought, on the very last day of that year, Mr. Pulcini sold a 50.1% stake to an British company which went by the same name, WNR Limited, but was controlled by two different shareholders.

LADY GAS FIELD

When she became co-owner of WNR Congo on December 31, 2013, Maria Paduano, nick-named Marinù, was a 36 years old law graduate (though not member of the Italian Lawyers Bar) known only as an exhibition organizer in Africa and as the wife of Domenico Bellantone. An influential ambassador, Bellantone has held the office of personal secretariat of Italy’s vice-foreign ministers since 2013 — being confirmed also by the last four governments— but he is not involved with the African gas business. The documents reveal that his wife got her stake in the field on her own through two British companies incorporated shortly before the deal, in 2012.

The man who mentions the name of "Marinù", in a curious digression on the records mistakenly calling her "Patuano", to prosecutors Milan is Vincenzo Armanna, a former ENI top manager currently one of the main defendants in the trial over the maxi-oil bribes (over one billion euros) paid between 2011 and 2012 in Nigeria. In April 2016, the defender speaks about her as "a person close to Roberto Casula", the current Chief Development, Operations & Technology Officer at ENI, who de facto ranks second in the corporation’s C-suite. Casula built a career in Africa as a loyalist to former CEO Paolo Scaroni.

Armanna speaks also of "a 2011 photography show sponsored by ENI with photos sent to Abuja via diplomatic cargo. The exhibition brought to the Italian embassy every important Nigerian personage. They spent half a million dollars.” Curators were Marinù Paduano and "Marta B., who is the wife of the then head of AISE", Italy’s military intelligence services, as in a statement issued by the Italian Foreign Affairs ministry. Both women also set up other exhibitions across Nigeria and Egypt.

Armanna then added that Casula and our 007 were "longtime friends", and that it was the two of them who pressed "strongly for the appointment of Gianfranco Falcioni as Italian honorary consul.” An entrepreneur settled in Africa, Falcioni played a quite surprising role in the ENI-Nigeria scandal. He is the owner of an offshore company that in 2011 was about to collect from the Nigerian government, on grounds never clarified, a full billion dollars paid by ENI — only to have the bank transfer rejected by Swiss bank BSI, which considered it a likely bribe.

Sifting through Armanna’s many allusive statements, one fact is a certainty: Lady Gas Field has links with ENI’s C-suite officer Casula in the form of business deals. Worth noting is her buying a fine property in Rome’s central district in March 2016: an attic of over 2200 square feet. After signing the offer, however, Ms. Paduano never followed up on with the contract registration procedure, but handed it to ENI’s executive officer. By signing the final contract with the original sellers in June 2017, Casula became the sole owner of the attic — and that is why the name Paduano as intermediary does not show in the cadastral records.

ENI hired Domenico Paduano, Marinù’s baby brother, in 2012. He is currently employed in the Mozambique branch of the Italian oil and gas multinational corporation, but is a resident of the UK.

AN ENGLISHMAN IN MONTECARLO

The fourth undisclosed shareholder of the Marine XI gas field is a British executive domiciled in the French- speaking tax haven, Alexander Haly, who heads several supply companies for the oil industries. In Congo, he is executive director of Petro Services, a company which statedly is a provider for ENI and Total.

When the anti-corruption watchdog organization Re: Common (the same that denounced the Nigerian oil scandal in Milan) asked for information to plot the interrelations with suppliers, including Mr. Haly’s companies, ENI denied any relation: "We have no contracts with Petro Services or with OSM Group in Congo.” OSM is a Norwegian corporation that entered in a joint venture with Mr. Haly’s company.

ENI here had the truth withheld from its shareholders. As a matter of fact, Mr. Haly had been working for the Italian oil and gas giant for at least ten years. A number of emails show that Petro Services has leased commercial ships from ENI in Congo since 2008. In May 2009, to request the payment of four monthly invoices, the English executive personally wrote to Roberto Casula, who answered: "Dear Mr. Haly, thank you for not having discontinued the service. ENI Congo will solve the problem ASAP. Our new director is fully on top of this.”

Mr. Haly had even closer relationships with other ENI executives in Africa. Ernest Olufemi Akinmade is an engineer who had worked for years for the Nigerian subsidiary of the Italian group before becoming the right-hand man of former Nigerian Oil minister Dan Etete: the key figure protagonist of the Nigerian mega corruption schemes that involved ENI and Shell. In 2011 it was Akinmade who, hiding behind an offshore company , represented Etete in the final negotiations for a super contract of over a billion dollars, which later vanished in a whirl of bribes. It is clear now that from June 2014 to April 2015 Akinmade himself became sole executive officer of the British WNR, Mr. Haly and Mrs. Paduano’s “safe”-company, who had managed it before him, from 2012 to 2014, besides being shareholders.

The Englishman in Montecarlo is also shareholder and advisor to Cap Energy, a British oil company that has hired several former ENI officers in West Africa. Cap Energy’s board of directors includes Pierantonio Tassini, who is also the company’s executive operations officer, and Mr. Haly. Tassini is an Italian top manager who has worked for ENI for more than 40 years in top positions in the gas industry in Africa and the Middle East. Within the company he is considered a loyalist to Claudio Descalzi, ENI’s current number one executive.

MS. DESCALZI'S PO BOX

Petro Services Congo, Mr. Haly’s contracting company for ENI and Total, is registered with a peculiar address: PO Box 4801 in Pointe Noire, the economic capital and the main commercial port of the country. This is exactly the same PO Box stated as domicile for the management of an offshore company, Elengui Limited, by its owner Marie Magdalene Ingoba, the wife of Mr. Descalzi, who is a Congolese citizen.

When L'Espresso revealed, drawing from the Panama Papers, that the lady paid $50,000 in 2012 to incorporate a tax-free company in the British Virgin Islands, the PO Box lost a client: OSM Congo. The company of Mr. Haly’s partner then moved its domicile from box 4801 to the box number 686 of a lawyers firm. As a rule of thumb, when a PO Box address is shared by the owners of different companies, the latter have also in common the consultant firm or trustee. Lady Descalzi stated that her offshore company, closed in May 2014, had nothing to do with ENI.

ENI AND THE COMPANIES OF THE REGIME

The Italian multinational has had a footprint in Congo since 1968, but it was in the 90s that it gather a leading role under the guidance of Mr. Descalzi, who began to climb the corporate hierarchy in Congo to become CEO of the local subsidiary in 1994. Today ENI extracts about a third of all Congolese oil, having overtaken French Total, which benefited from the colonial heritage. To do so, ENI benefitted from tailwinds: new extensive discoveries of hydrocarbons and an important network of relations. Jerome Koko, the current CEO of the state oil company SNPC, graduated in engineering in Rome. He was hired in 1984 by ENI Congo, and was at the right spot to become Mr. Descalzi’s successor.

According to Transparency International, French Congo ranks as one of the most corrupt countries in the world. Several investigations of the prosecutor offices in France, Portugal, Italy and San Marino are ongoing, and all accuse top African government officials of using shell companies to divert for personal benefit the profits the country produces. The British High Court of Justice blacklisted, already in 2005, the company AOGC (African Oil and Gas Corporation) for misappropriating and hiding abroad public funds to the tune of at least $472 million. In the records of the World Bank the company is still listed as a "regime company" used to steal wealth from the Congolese population.

Keeping this in mind, it stands out that, as shown in the Paradise Papers, WNR Congo (the company owned by the three Italians and an Englishman in Monte Carlo) bought its 23% of the Marine XI field from AOGC. The deal came to being in four months from scratch. On December 26, 2012 AOGC (which already had owned a 10% stake since 2005) bought another 26% stake from Russian company Vitol. On March 25, 2013, AOGC re-sold a 23% to WNR Congo, keeping a minority stock of shares. The documents collected from the Mauritius Island reveal that the offshore of the three Italians paid no more no less than $15 million for a stake that is actually accounted for in the books at a $430 million handle.

Since 2014, AOGC partnered with ENI and TOTAL with no intermediaries in deals managed by the Congolese government. The two multinational companies had had for years licenses to exploit several very rich fields. In 2014, the permits were renewed but not fully. ENI and TOTAL lost significant shares that the government transferred to AOGC. The Italian company controls four extraction sites (Foukanda, Mwafi, Kitina and Djambala), where AOGC obtained shares ranging from 8 to 15%. TOTAL manages three other fields, of which ENI is only a shareholder. In these, the French oil giant relinquished to 26%, whereas the Italian group gave up 14%: these shares too went to AOGC and two other secretive societies. The amounts paid by AOGC to enter these fields businesses never became public.

Finding out that the Italian group had become partner of the "company of the regime" brought about in 2015 a strong clash at the top floor of ENI between economist Luigi Zingales and ENI’s top official Claudio Descalzi in person. At the shareholders' meeting, when asked whether AOGC had been ENI‘s choice or rather imposed by the Congolese government, Mr. Descalzi replied: "We did not choose it.” The Italian group, therefore, seems to have undergone an imposition by the Congolese government.

L'Espresso, however, found out that ENI and TOTAL, in those very months, obtained the renewal of those licenses and new ones worth billions under very special conditions. Having had already several years of activity behind when the old ENI and TOTAL permits expired, the Congolese government could have assigned them to the state company, the experts consulted by L'Espresso explained. Instead, with a presidential decree, the government reassigned the licenses to the two oil multinational corporations in exchange for a "bonus", including AOGC in the deal. At that time ENI told L'Espresso that it had paid $22 million to renew the four licenses. In that year’s balance sheet, however, there is no record of the bonus. It shows on the 2016 budget but the amount ENI writes in is different: €8.6 million for three licenses (no information could be retrieved about the fourth license as of today).

In theory, AOGC as well would have had to pay its part of the bonus to the government, publicly stating the amount to abide to Congolese law. In fact no amount was ever disclosed. This can be explained twofold: either the Congolese government received the bonus without disclosing it, and so violating its own law; or AOGC did not pay its part.

BRIBES, VILLAS AND CHAMPAGNE

AOGC always had very close ties with the Congolese government. It was founded in 2003 by Denis Gokana, who is the current president of the state-owned oil company SNPC, as well as special energy advisor to president Sassou Nguesso. According to several documents, AOGC has been used for years as a private ATM of the regime. In 2004 the oil company already paying for shopping sprees of Christel Sassou Nguesso, the son of the president, currently a top manager of SNCP, like in excess of $250,000 to boutiques in Paris, the organization Global Witness revealed. A document obtained by Mediapart journalists from the French police reports of another bank payment of $341,500 transferred from AOGC that same year to a French haute couture maison. The motive is handwritten: "Bonifico Sassou Nguesso + Bouya.”

Jean-Jacques Bouya, a cousin of the president, is one of Congo’s most influential politician. He has held the office of minister of the Territory since 2012, and as such he also heads large infrastructure projects. His right-hand man is Dieudonné Bantsimba, his Chief of staff and director of the Agency for Large Infrastructures (DGTT). Precisely his department is now at the center of a large corruption scandal unveiled by the San Marino Prosecutor's Office. The first trial ended this last January with a six-year sentence for Philippe Chironi, a French trustee accused of money laundering to the benefit of the Congolese regime.

Chironi, who appealed the sentence, ran a network of offshore companies that, according to the prosecutor’s, allowed the Sassou Nguesso family to transfer at least 83 million dollars to Europe. That is money taken away from the Congolese population. Diverted to bank accounts in San Marino, it is then spent to buy anything from luxury villas and apartments in Paris and in the United Arab Emirates, crates of champagne, crocodile shoes, jewelry and watches to Carrara marble and Brianza furniture. The flow of money exited Congo through the very DGTT, the agency headed by Mr. Bantsimba.

Mr. Bantsimba, after Mr. Gokana, became shareholder of AOGC, the company partner of ENI — and the ATM paying for the luxuries the Congolese regime indulges in, as well as the seller of the gas field to Italian offshore company WNR Congo.

The documents of the Paradise papers stop in October 2015. At that time WNR Congo that managed the Marine XI gas field was still in the hands of the three Italians and the Englishman in Montecarlo. Over the last few months, the Swiss group Mercuria, which had issued all loans, begun negotiating the acquisition of the offshore companies in the Mauritius Islands. The records do not show whether the Italians sold the companies and, if so, how much they made.

ENI has always denied any complicity with the mega corruption schemes in Africa. However, what is now known about the issue in Congo pushed the researchers at Re: Common to launch a fresh research for a new denunciation: "In the last two shareholder meetings we asked ENI about the facts in Congo, but received only elusive and far too uncomplete answers. The truth seems to be quite different. In light of the recent developments, including judiciary ones, we share the position of former councilor Zingales: ENI needs an independent external commissioner with full powers to investigate.”